When it comes to writing great software, Safety First! Writing great software isn’t easy...especially when you’ve got to make sure your code

works, and make sure it keeps working. All it takes is one typo, one bad decision from a co-worker, one crashed hard drive, and suddenly all your work goes down the drain. But with version control, you can make sure your code is always safe in a code repository, you can undo mistakes, and you can make bug fixes—to new and old versions of your software.

Project - BeatBox Pro :

In this chapter, we start with a original existed project - BeatBox Pro. The customer want you to extend the functionalities of it. And you have already collected user stories and divided into tasks as well (refer to ch4). Unfortunately, things not go smoothly and encounter some problems. Here we have Ken and Bob to joined this project. After Ken and Bob upload their codes into Server, the merge disaster occurs and demo failed to our customer...

Let’s start with VERSION CONTROL :

Keeping track of source code (or any kind of files for that matter) across a project is tricky. You have lots of people working on

files—sometimes the same ones, sometimes different. Any serious software project needs version control, which is also often called configuration management, or CM for short.

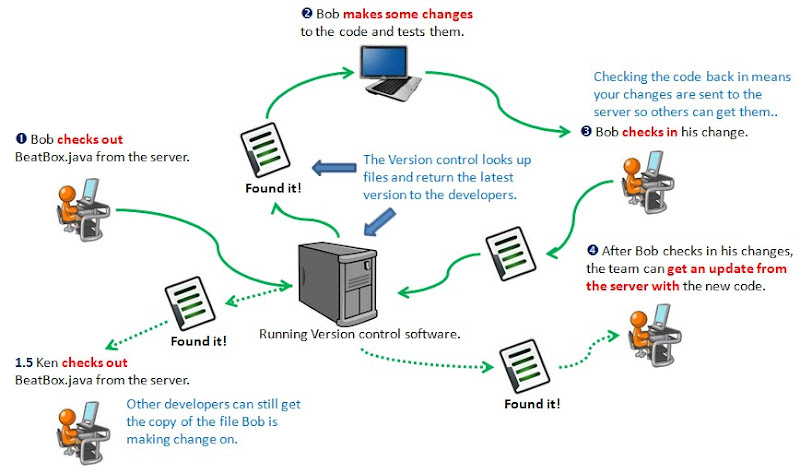

Version control is a tool (usually a piece of software) that will keep track of changes to your files and help you coordinate different developers working on different parts of your system at the same time. Here’s the rundown on how version control works :

First set up your project :

The first step in using a version control tool is to put your code in the repository ; that’s where your code is stored. There’s nothing tricky about putting your code in the repository, just get the original files organized on your machine and create the project in the repository :

1. First create the repository

you only need to do this once for each version control install. After that you just add projects to the same repository.

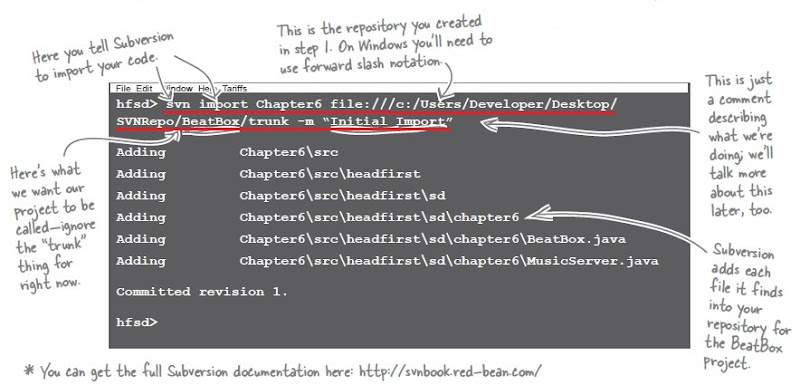

2. Import your project

Next you need to import your code into the repository. Just go to the directory above your code and tell your version control server to import it. So, for your BeatBox project, you’d go to the directory that contains your beat box code.

...then you can check code in and out :

Now that your code is in the repository, you can check it out, make your changes, and check your updated code back in. A version control system will keep track of your original code, all of the changes you make, and also handle sharing your changes with the rest of your team.

First, check out your code (normally your repository wouldn’t be on your local machine) :

1. Check out your code

To check out your code, you just tell your version control software what project you want to check out, and where to put the files you requested.

2. Code modification

Now you can make changes to the code just like you normally would. You just work directly on the files you checked out from your version control system, compile, and save.

3. Commit change

Then you commit your changes back into the repository with a message describing what changes you’ve made.

Manage Conflict :

Suppose Ken check in his code (with commit) to implement Send Poke, and then Bob would change his code, and try to commit his work on Send Picture :

If two people make changes to the same file but in different places, most version control systems try to merge the changes together. This isn’t always what you want, but most of the time it works great.

- Nonconflicting code and methods are easy

In BeatBox.java, Ken added a playPoke() method, so the code on the version control server has that method. But Bob’s code has no playPoke() method. In a case like this, your version control server can simply combine the two files. In other words, the playPoke() method gets

combined with nothing in Bob’s file, and you end up with a BeatBox.java on the server that still retains the playPoke() method. So no problems yet...

- But conflicting code IS a problem

But what if you have code in the same method that is different? That’s exactly the case with Bob’s version of BeatBox.java, and the version on the server, in the run() method. If two people made changes to the same set of lines, there’s no way for a version control system to know what to put in the final server copy. When this happens, most systems just punt. They’ll kick the file back to the person trying to commit the code and ask them to sort out the problems. (That means more merge work to do!)

Bugs in released version 1.0 while 2.0 is ongoing :

Thinks of the case you found a bug in released version 1.0 and now you are going on version 2.0. You don't want to roll back to version 1.0 to fix that bug because you have made a log of code change for version 2.0. What's more worst, how do you figure out the code exactly in version 1.0? So we need to separate them somehow...

Ps.

- By default, your version control software gives you code from the trunk

When you check out the code from your version control system, you’re checking it out from the trunk. That’s the latest code by default and (assuming people are committing their changes on a regular basis) has all of the latest bugs features.

- Version control software stores ALL your code

Every time you commit code into your version control system, a revision number was attached to the software at that point. So, if you can figure out which revision of your software was released as Version 1.0, you’re good to go.

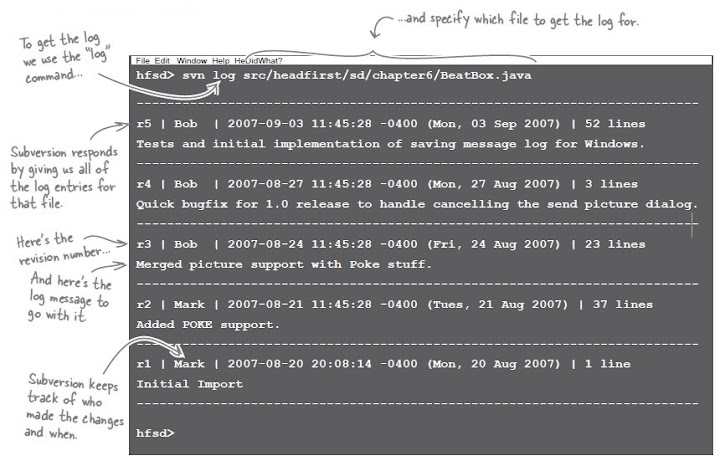

- Good commit messages make finding older software easier

You’ve been putting nice descriptive messages each time you committed code into your version control system, right? Here’s where they matter.

Just as each commit gets a revision number, your version control software also keeps your commit messages associated with that revision number,

and you can view them in the log :

Bug fix (Part 1) :

Now we are going to fix bug found in version 1.0. First is to check out the version 1.0 code and fix. Afterward, commit the code change...

1. Check out v1.0

Once you know which revision to check out, your version control server can give you the code you need :

2. Fix bug in code checked out

Now you can fix the bug Bob found...

3. Commit code change

With the changes in place, commit the code back to your server...

Since we check out the old version code, we can't commit to current version which will cause some previous done-change missing.

Bug fix (Part 2) - Tag your versions :

The revision system worked great to let us get back to the version of the code we were looking for, and we got lucky that the log messages were enough for us to figure out what revision we needed. Most version control tools provide a better way of tracking which version corresponds to a meaningful event like a release or the end of an iteration. They’re called tags.

Let’s tag the code for BeatBox Pro we just located as Version 1.0 :

1. Create tag directory

First you need to create a directory in the repository for the tags. You only need to do this once for the project (and this is specific to Subversion; most version control tools support tags without this kind of directory).

2. Move specific version to the tag directory

Now tag the initial 1.0 release, which is revision 4 from the repository.

So what did that get us? Well, instead of needing to know the revision number for version 1.0 and saying svn checkout -r 4 ..., you can check out Version 1.0 of the code like this:

And let Subversion remember which revision of the repository that tag relates to.

Bug fix (Part 2) - Branch :

The tag is a snapshot of the code at the point you made the tag. You don’t want to commit any changes into that tag, or else the whole “version-1.0” thing becomes meaningless.

We can use the same idea and make a copy of revision 4 that we will commit changes into; this is called a branch. So a tag is a snapshot of your code at a certain time, and a branch is a place where you’re working on code that isn’t in the main development tree of the code.

1. Create branch directory

Just like with tags, we need to create a directory for branches in our project.

2. Copy specific version to branch directory

Now create a version-1 branch from revision 4 in our repository.

Tags, branches, and trunks :

Your version control system has got a lot going on now, but most of the complexity is managed by the server and isn’t something you have to worry about. We’ve tagged the 1.0 code, made fixes in a new branch, and still have current development happening in the trunk. Here’s what the repository looks like now :

Ps.

Bug fix (Part 2) - Fix bug :

When we had everything in the trunk, we got an error trying to commit old patched code on top of our new code. Now, though, we’ve got a tag for version 1.0 and a branch to work in. Let’s fix Version 1.0 in that branch :

1. Check out branch code

First, check out the version-1 branch of the BeatBox code :

2. Fix bug

Now you can fix the bug Bob found...

3. Commit fix

...and commit our changes back in. This time, though, no conflicts:

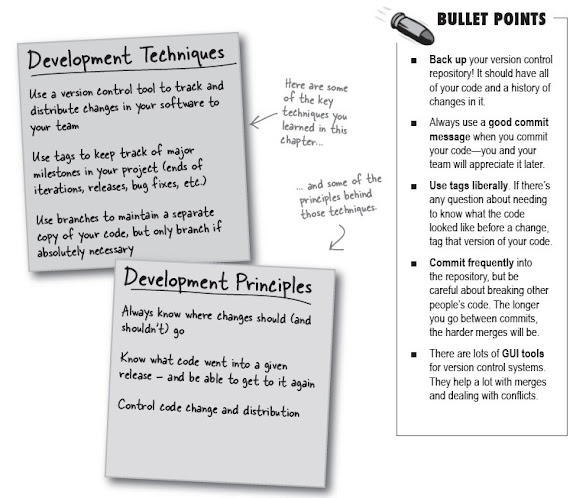

Tools for your Software Development Toolbox :

Software Development is all about developing and delivering great software. In this chapter, you learned about several techniques to keep you on track. Below is the tool tips for your reference :

Supplement :

* SVN 基本指令教學

沒有留言:

張貼留言